There’s a strange shadowboxing quality to the whole abundance debate. While on the surface two liberal factions seem to be at odds over technical economic questions, in reality there’s an undercurrent of a struggle over what exactly the left should be. The abundance crowd isn’t simply arguing for deregulation in housing, and it’s not a coincidence that they are often the same people who think DEI and cancel culture have gone too far, and many of the pro-Palestine protests are counterproductive.

Nonetheless, there is value in the more specific debates, as housing is the largest single household expenditure in the United States, and prices have shot upwards almost universally across developed nations. Broadly speaking, there are two factions fighting over the affordability question: those who blame business, and those who point their finger at zoning. The antimonopoly types who believe business is the problem will concede that maybe land use regulations should be less stringent, but quickly follow up by saying that’s not where the focus should be. As Zephyr Teachout told Ezra Klein during an appearance on his podcast, “I don’t need to fight you on particular housing policies that you’re deep in the weeds of, on zoning policies.” Antimonopoly activist Basel Musharbash similarly begins a recent essay by saying he does indeed think that zoning laws need to be reformed, but proceeds to heavily imply that this isn’t as important as housing market consolidation. He has an ally in JD Vance, who goes further than his counterparts on the left by blaming BlackRock, narrowing his focus to a single company.1

Klein and Thompson have a straightforward argument, one favored by the standards of Occam’s Razor. Restrict supply, prices go up. It is difficult to imagine a simpler economic idea. To the anti-monopoly side, in contrast, the laws of supply and demand aren’t working as well as they should because a few big players control the housing market.

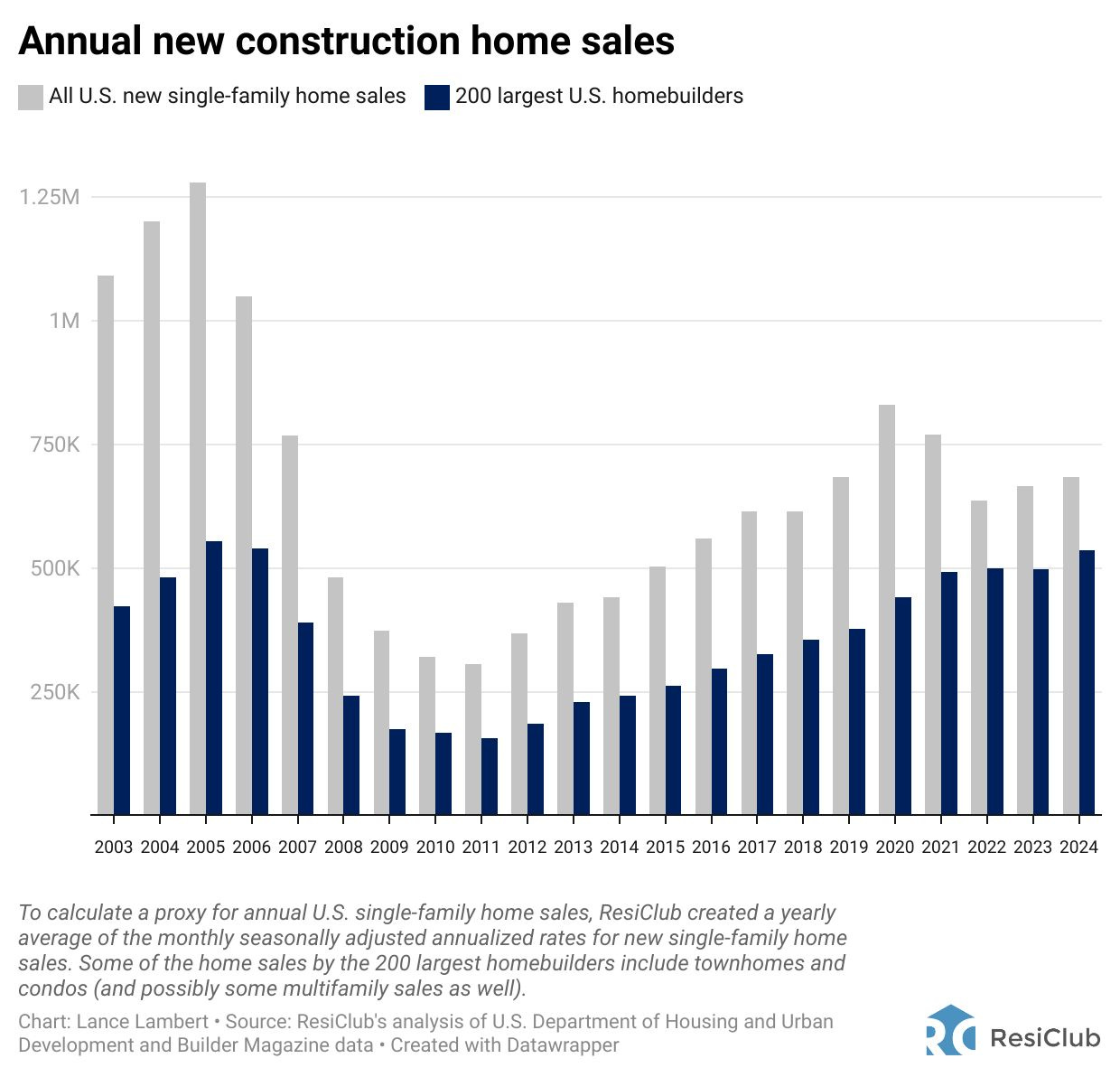

Matt Stoller points out that in 1990, the ten largest homebuilders controlled only about 10% of the market. But by 2018 their share had grown to around a third, with the problem being worse in some areas. He attributes rising housing costs in part to these intermediary firms — developers who benefit from cheap financing and outsource construction to subcontractors — arguing that their dominance contributes to inflated prices.

Yet are we even at the level where this is an issue we should worry about? The Herfindahl-Hirschman Index was developed to measure market concentration in particular industries, and is used by the Department of Justice in reviewing mergers. The details need not concern us here, but note that the DOJ considers a score of 1,000 to be moderately concentrated, with a number above 1,800 indicating high concentration. Relying on Builder Magazine’s top 200 builders of 2024 in terms of total closings, we get a score of 658 for the housing industry. This is low concentration even by the standards of current guidance, which is stricter than it used to be. Before December 2023, the benchmarks for moderate and high concentration were 1,500, and 2,500. Regardless of which measure we use, the housing market is highly competitive. And even the 658 number exaggerates the issue, since it only takes the top 200 builders as the entire market.

The US Census Bureau does its own calculations for various industries. For the category of real estate, it gives an HHI score of 12.8. The category “real estate and rental leasing” is at 19.6, “real estate and property managers” at 63.3, and “residential building construction” at 54.3. No matter how we look, the results tell the same story.

Stoller correctly points out that the market is often more concentrated at a local level. Yet I think this is a good example of how those against monopolies can play with what they consider the size of a market to get the results that they want. If there is a high level of concentration in one locality and this harms consumers, then other firms can move in and take advantage. Sometimes this doesn’t happen due to barriers to entry, but the biggest barrier to entry in the housing market is by far zoning laws, so we’re right back to that being the main issue we should worry about. Real estate is an industry where personal relationships and familiarity with local conditions matter a great deal, and the more barriers in place, the more that cronyism and corruption can flourish.

Still, even at the local level, there doesn’t appear to be evidence that concentration at this point rises to the level of requiring government intervention according to conventional standards of judgment. Musharbash’s essay focuses on the Dallas-Fort Worth-Arlington area. Based on his numbers for the top ten builders in the region, who collectively control 61% of the sector, we still see low levels of market concentration according to the HHI score even when taking this more local perspective.

When Stoller says ten firms control a third of the industry nationwide, that may sound bad without any additional context. But to see why we shouldn’t worry about this, one must understand the reason that market consolidation can be a problem in the first place. The main potential issues are a lack of competition and the possibility of coordination, whether explicit or not. Companies may have little incentive to compete on price or quality, or come to see mutual benefit in avoiding such competition in the first place. But the ability to coordinate effectively depends in a straightforward way on the degree of concentration. It is relatively simple for one or two firms to align their behavior, even tacitly; it becomes significantly harder when there are four or five relevant players. In the homebuilding sector, even if the top ten firms colluded against consumers, they still wouldn’t control half the market. Just imagine what coordination would look like in this case, and how easily it could unravel. The most straightforward way to make money under such circumstances is to lower your prices or increase the quality of the product offered, rather than form a tacit cartel aimed at squeezing consumers. By standard measures, homebuilding is one area where the standard market forces of supply and demand should operate normally.

Here’s a chart from Musharbash showing that the 200 largest homebuilders now control a healthy majority of the market nationwide.

But 200 is a lot of firms! No economist believes that the optimal amount of concentration in a market should approach zero. Some companies will more efficiently produce a good or service, therefore grabbing more market share, and there are economies of scale, in which larger firms can do some things better than smaller ones. If you think 200 firms making up a majority of a sector means that the normal laws of supply and demand don’t work, you would probably find it hard to imagine them working under any circumstances. To me, the existence of 200 companies sounds like it would create a lot of competitive pressure, and they don’t even make up the entire market. I don’t think we even have a large enough population of entrepreneurs to ever satisfy the anti-monopoly types that every industry has an adequate level of competition. It’s interesting that when you read antimonopoly authors, they often complain about the very fact that large corporate owners can build cheaper due to structural advantages. But this is what we want! They also blame better access to capital, yet again, if the market is open, the correct answer to that is for someone else to come along and seize the investment opportunities opened up by market consolidation.

If market consolidation were the main problem, you would expect areas with less of it to do better on affordability. Neither Stoller nor Musharbash attempts to show this, and their silence here is telling. Conducting the research on their behalf, I found this National Association of Home Builders report listing the five metropolitan areas with the most concentrated housing markets to be Indianapolis-Carmel-Anderson, IN; Las Vegas-Henderson-Paradise, NV; Columbia, SC; Jacksonville, FL; and Riverside-San Bernadino-Ontario, CA. These aren’t exactly the places we think about when discussing housing affordability.

This brings up a more general point, which is that the abundance side spends a lot of effort trying to explain variation between different regions and localities, while the anti-monopoly side becomes visibly uncomfortable when you bring such questions up. M. Nolan Gray shows that housing affordability is primarily a blue state issue. We in effect invented the “high-cost” state. Klein and Thompson in their book stress that states controlled by Republicans are winning on housing.

Texas has been the single largest beneficiary of California’s housing crisis. And that is, in part, because Texas is California’s mirror image on housing. The Austin metro area led the nation in housing permits in 2022, permitting 18 new homes for every 1,000 residents. Los Angeles’s and San Francisco’s metro areas permitted only 2.5 units per 1,000 residents. In our political typologies, it is liberals who embrace change and conservatives who cling to stasis. But that is not how things work when you compare red-state and blue-state housing policies.

When someone makes an argument that goes against their ideological and partisan commitments, it is a reason to take them seriously. Klein and Thompson are Democrats who say Republicans by implementing pro-market policies are getting right something they consider fundamentally important. Meanwhile, the arguments of the anti-monopoly crowd seem to represent a classic case of “when you have a hammer, everything looks like a nail.” I once started reading Stoller’s book BIG as it was recommended to me by some people, and, independently of whether I agreed or disagreed with specific arguments, I saw red flags in almost everything about how he engaged with and presented ideas. Basically, the world could be divided into bad people who support big business, and good people who don’t. Good people with good intentions never cause negative unintended consequences, and the bad people never get anything correct on accident. A thinker gains credibility with me when they acknowledge potential tensions or shortcomings in their worldview, and lose it when they seem to be trying to pigeonhole everything into a simplistic story with predetermined heroes and villains.

Of course, we shouldn’t decide our opinion on the housing issue based on the observation that abundance types show the hallmarks of good epistemological standards and the antimonopoly crowd doesn’t. If we simply determined who was correct based on who the good and bad people are, we wouldn’t be any different from those who simply want to blame big business for everything. What matters in the housing issue is that the abundance side is correct on the merits, while its opponents are wrong. The fact that one faction seems to be so clearly motivated by ideological commitments and a predetermined narrative should nonetheless be kept in mind when trying to understand what the broader debate on the left is about.

This rant would distract from the main essay, but here I need to return to a point that I’ve made before, which is that right-wing economic populism is similar to left-wing economic populism, just more incoherent, since it is aimed at low information conspiracy theorists rather than highly-informed college graduates. If you’re reading this essay and glad that I’ve owned the libs by arguing for free markets, keep in mind that the successor to Trump, who you probably support, agrees with them on these fundamental issues, and presents even worse reasons for his positions.

Interactions with anti-Abundance types online are interesting. I had wondered out loud why people who claim to want more green energy oppose a movement that wants to deregulate the construction of green energy and push it forward with the government, then received this reply:

> Yeah cuz if modern political history tells us anything, you'd just get the first item and the rest just can't get done because of the parliamentarian or whatever. Yall really are Charlie running at the football over and over

A lot of distrust appears to be driving anti-Abundance types, and it's both distrust in liberals and distrust in the American political system. Like Musharbash, they don't really think making more green energy or housing by deregulating it would be bad. They just see the word "deregulation" and have an explosive knee-jerk reaction against it, and come up with a story about how the bad forms of deregulation in their imagination will happen and the good parts of the Abundance agenda won't.

Is that story plausible? Sure it is. Compromises have to be made all the time. A compromise on an issue like this, with deregulation and no additional green energy funding, would sometimes lead to more coal and gas rather than less. But the long arc of power construction history appears to be bending towards green energy, and regulations are a major obstacle in its movement.

Many problems with the modern left can be understood by thinking of the modern left as a social club. For people who are more neurotic than average, more insecure than average, and less accepting of traditional gender norms than average, the modern left is a 'social bubble' (on college campuses, think tanks, so on and so forth) where people who would otherwise struggle socially can make friends and identify with an in-group. Social clubs definitionally adhere to the lowest common denominator: if only the smart people in the club get some idea, it gets viewed as offensive and elitist to shamelessly promote it to the rest of the people in the group. There are people on the left who are smart enough to understand Klein's idea, but when push comes to shove they are going to prioritize the social cohesiveness of their in-group over literally adopting the most factual belief possible.